Often Tradition and Innovation are just two sides of the same coin. This is especially true in the art of tracking.

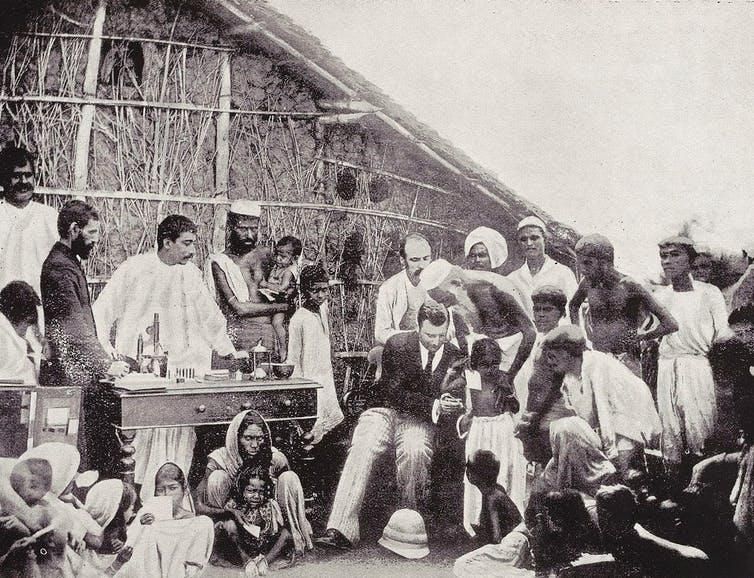

The actual Tactical application of Tracking owes a lot to a particular time in history. Colonialism itself paid tribute to the most ancient and primitive form of this skill.

In this article, we will dive deeper into it, thanks to the contribution of Prof. Timothy J. Stapleton, Department of History, University of Calgary (Canada).

Prof. Stapleton is author of the following books, just to name a few:

“No Insignificant Part: The Rhodesia Native Regiment and the East African Campaign of the First World War”- Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2006.

“Warfare and Tracking in Africa, 1952-1990” – London: Pickering and Chatto/Routledge, 2015

“War and Conflict in the Twentieth Century” – London: Routledge, 2018

“The word ‘ivory’ rang in the air, was whispered, was sighed. You would think they were praying to it. A taint of imbecile rapacity blew through it all, like a whiff from some corpse. By Jove! I’ve never seen anything so unreal in my life. And outside, the silent wilderness surrounding this cleared speck on the earth struck me as something great and invincible, like evil or truth, waiting patiently for the passing away of this fantastic invasion.”

Joseph Konrad, Heart of Darkness, 1899

Late 1800: all of the most powerful European Countries (France, England, Portugal, Belgium, Spain, Italy, Germany) started to commit themselves to colonization, or at least creating outposts in so-called “3d World” countries (which are less economically developed, often politically unstable), especially in the African Continent, seen as a cornucopia full of treasures to be conquered.

Back in the day, “[…] Europe’s expansion is remembered as exploration, and the men who helmed ships that landed in foreign countries — and proceeded to commit violence and genocide against native peoples — are remembered as heroes […]” (J. Osman).

Think, for example, of Christopher Columbus in 1492. We all know that story.

Later on, during the 19th Century, began the so defined “Scramble for Africa“.

By establishing long-term or even long-lasting outposts the European Countries (France, England, Portugal, Belgium, Spain, Italy, Germany), started to penetrate most of the African territory, creating several laws with the aim to exploit the existing abundance of materials (especially precious metals).

France: mostly in the Northwest of the African Continent (Mauritania, Senegal, Benin, Niger, Chad,..)

England: Nigeria, Rhodesia, Kenya, Sierra Leone, ..

Portugal: Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea- Bissau, Mozabique, Equatorial Guinea..

Belgium: Congo, Ruanda..

Spain: Sahara area, Morocco, Spanish Guinea

Italy: Libia, Etiopia, Eritrea, Somalia..

Germany: German West Africa (Cameroon, Chad, Ghana, Togo..), Namibia, German New Guinea, German East Africa

This is just to provide you a generic synopsis. Most modern countries of Africa knew a period of colonialism, which became an often contrived and unwilling relationship with the Mother Country.

The Colonies faced a long period of dishonesty: the indigenous people suffered from slavery, forced to obey to the language, the imposed habits and the rules of their dominators until small groups of organized guerrilla began to rebel, asking for independence. Times were changed and the necessity to rise as a newborn recognized state echoed like a premonitory storm in all the Colonies. We all know what happened next, and how some Countries are still, by economical convenience, and die-hard colony, tied to their Mother Country.

At this point some of you may ask how the art of Tracking has to do with Colonialism.

Let me explain this to you through the words of Professor Stapleton, who released an exclusive interview with me:

“[…] Many years later, as an historian of war and society in Africa, I observed that academic and popular book and other works on counter-insurgency campaigns in Africa mentioned tracking as a central activity but did not discuss specific training or tactical doctrines around its use. The British officer Frank Kitson, who served in Kenya during the 1950s and later commanded land forces UK, called it the most important skill to deploy during counter-insurgency operations as a way to locate and eliminate elusive insurgents […]” (T.J.Stapleton)

Natives used tracking all of their life, so came the necessity to counteract them with their own very weapons. And on their terrain, from the bush to the jungle. In such a sense, it became mandatory. Through close contact with indigenous, Western Civilization started to learn how to define this skill, applying it to a different scenario. Tracking in Africa can be extremely easy or drastically tough, it all depends on several factors and pitfalls too: the terrain, the environment, the weather conditions, the physical fatigue, dangerous animals the deprivations and so on.

Not to mention the counter tracking techniques employed by the guerrilla: ” […] they have to be elusive using the environment to conceal themselves while they engage in politicizing the masses and conducting hit-and-run attacks on enemy weak points. While counter-insurgent forces then use tracking to try to locate guerrillas, the guerrillas can use anti-tracking techniques in attempting to avoid detection. […]” (T.J. Stapleton)

In further articles, we will analyze the most common anti-tracking techniques employed in that specific period by the local guerrilla. Often they seemed to be unreachable, thanks to the knowledge of their territory and their abilities in evading the Trackers’ pursuit.

Equally, many were the CTU (Combat Tracking Units) which stood out for skills, successes achieved and their expertise.

Again, Professor Stapleton revealed his personal thoughts on them:

“[…] With reference to conflicts in late 20th Century Africa, I suspect that the South West African Police Counter-Insurgency Unit also known as Koevoet that fought in South West Africa (now Namibia) in the very late 1970s and 1980s has a good claim to that title. They combined excellent tracking knowledge and skills, mostly from among the Ovambo people, with mechanized vehicles and really effective close air support. The environment of northern SWA was also important in enabling Koevoet to bring all these elements together but certainly they became extremely efficient in using tracking to quickly locate and kill insurgents. At the same time, their enemies, the South West African Peoples Organization (SWAPO) insurgents, responded by becoming highly skilled in anti-tracking and many of them were also from the Ovambo community so they had the same skills. As I explain in my book on the subject, the conflict in northern Namibia in the 1980s largely became a trackers’ war with each side trying to out-track or out-counter-track the other. It is also important to recognize here that given the nature of this conflict, Koevoet became a highly controversial force accused of human rights abuses. But in terms of tracking, they have a claim to the top spot. Some Koevoet veterans went on to conduct tracking or other operations in more recent counter-insurgency campaigns as private contractors […]”

Two parties. One terrain. Same weapons. We will see in the next article how they engaged the fight applying the Art of Tracking.